How Long Does It Take to Become Good At Photography?

I am not sure there is a definitive answer, but it does take a while.

When Malcolm Gladwell wrote his book, "Outliers,” he had a chapter devoted to the "10,000-hour rule,” which implied that it took 10,000 hours of practice to become good at something.

I think this single criterion has been fairly criticized by people who think that it was too simplistic, and even he has said that most who quote that are doing so out of the real context of it, but he was clearly making a statement regarding the absolute importance of practicing one’s skill.

What was fundamentally lacking in the oft-quoted “10,000 hours to achieve mastery” meme, was the unforgiving truth that if you practice something incorrectly for 10,000 hours, you will master doing it incorrectly.

Practice doesn’t necessarily make what you do perfect, it simply makes it automatic. Automatically playing it wrong will not be a triumph if you are working on a Beethoven sonata; it will make it nearly impossible to correct it without a struggle.

“Perfect practice for 10.000 hours” is the best way of thinking of the often-stated meme.* But what does “perfect practice” mean?

To do something well, I believe we need to concentrate on three different aspects of learning how to do it. The mechanics of it, the reason for it, and the personal execution of it.

The mechanics are lighting and exposure and composition and… you get the idea. How the camera, sensor, and lenses work together to form an image is the technical implementation. A capture. A shot.

This can take the form of trial and error, self-study, workshops, practice, and, well, schools. (I am not excited about “photography schools” these days. Save your money and just do it.)

The problem with only trial and error and self-study is that we may not learn the optimum way of doing something, and this can lead us to “practice it wrong” for a lot of those 10,000 hours. Not a good place to be. Working with learning technical stuff means getting feedback on the technical stuff.

Feedback is what was missing from the original understanding of the rule. You must get competent, qualified, and customized feedback. One-size-fits-all critiques are useless. You are not a machine.

So how do we do that?

Find a mentor, a group, a select tribe of photographers that can look at what you did technically and make positive suggestions. If it is not sharp, they can help you understand what may be going wrong. If the composition could be better, they will push you to discover ways to possibly do it better.

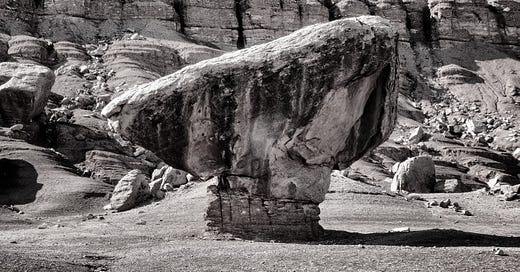

Many times this takes the photographer to a place of self-measurement. In order to know if it is working for them, they will compare their work with the work of an established photographer already found to be excellent. Want to learn large format black and white landscape? Perhaps studying the work of Ansel Adams, John Paul Caponigro or John Sexton may help you find your technical ‘base point’.

Once we have found it possible to make a ‘good quality’ image, we begin to be more selective in what we shoot since we are now looking for the reason to shoot it. This is the part of the process where we narrow our vision down a bit from shooting everything we see to making choices about subject matter, genre, presentation, and our personal style.

This is usually a longer process than the first. Building the body of work without a full reference to our own work means that we may have influences that are heavily invading our work. It can be derivative, similar, and in some ways a natural copy of those photographers we studied heavily in the first phase of the process.

We measure our work against other photographers for technicality and resonance. Does it have the same tonal quality as so-and-so? Does it look too much like her work, or is it more of a collection of watered-down copies of that other guy’s work? The struggle is real. In photography, it can become extremely easy to copy a technique, style, and genre approach. Too easy, unfortunately, and that will not change anytime soon.

Our next phase is when we get personally frustrated by making photographs that are even partly derivative or marginal copies and we start to stretch for our own vision. A style that ties all of our work together — and while technique and reason are always a hugely important part of it, the reality is that this last phase is all about choices.

The technique we have down. The subject matter we know. The presentation is second nature… NOW we have to use all we know to begin to develop a body of work that makes all of the images tie together into our own vision.

Some photographers think I mean that your work has to be 100% unique, and that is not it at all. It simply has to be 100% authentically YOUR work. If your work resembles someone else’s but is 100% authentically yours, that is fine. There are many landscape shooters who have the same subject and similar style… but many of them will approach the same subject with a slightly different perspective, point of view, angles, or any number of possibilities.

The similarities are not important, the difference is.

I usually quote the great jazz trumpet player Clark Terry:

“Imitate. Assimilate. Innovate.”

Three parts of a somewhat complex process are synthesized down into three simple words. However, each word is nearly a book unto itself on the process of learning an art.

How many hours will it take? I don’t know. You don’t know, nor should you think about it in that macro-managed sort of way. To do so puts a hierarchy on the irrelevant aspect of time. It is not about the hours… it’s not about the number of photographs you take.

It is about the process… and these processes can take different amounts of time for different people. Some will find the technical part to be a piece of cake while others will struggle with it. Learning the tools may take some folks longer. The best way to overcome that hurdle is to make photographs as often as possible and get as many qualified critiques as you can.

You are you. You are uniquely you. Your approach will be done the way you want it to be done. The assimilation phase can last as long as you choose to work there. If you look around, you will see that — unfortunately — many photographers decide to stay there. It can be warm and comfortable just doing what works over and over again.

But once you decide to push beyond the easily attained second level, the real work begins anew. Finding a voice, refining your style, creating unique imagery puts you in a vulnerable position. Unlike the assimilation phase, your work will not have the baseline comparison of the work you assimilated to use to justify and understand it.

And to add to the fun… heh… these different phases overlap each other. We are constantly working on technical even as we are producing a unique body of work in our own style and still being influenced by the artists we admire.

Don’t worry about the 10,000-hour or 10,000-photo rules. They aren’t rules, but more a set of guidelines to remind you that nothing will make you better than a focus on doing the work, having the work evaluated, and doing more work.

*Oh, and by the way, nobody knows how many hours it takes or has counted it out. It is meant as an allegory that, in order to do something at the expert level, one must do it a damned lot of times — correctly.

You can find me at my website: www.dongiannatti.com

I am a photographer, designer, and photo editor. You can find me at my self-named website or at Project 52 Pro System where I teach commercial photography online. This is our tenth year of teaching, and it is the most unique online class you will find anywhere.

Check out my newsletter and community at Substack. We are new, but growing.

You can find my books on Amazon, and I have taught two classes at CREATIVELIVE.

One more thing... on the subject of practicing correctly, there's this "thing" out now called "Deliberate Practice." It's pretty much parallel to what you are talking about here. Might I suggest an excellent read on the topic?... a book entitled, "Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise" by Anders Ericsson. About $14 on Amazon for the paperback version.

I really enjoyed this article. I was thinking the other day about this very thing, and that I am feeling that I am FINALLY just getting to the point that I know enough to even BEGIN learning how to do real photography, if you know what I mean. I find myself going through spurts of growth, where I might go two years with no real noticeable growth, then in a matter of a few weeks I've reached "the tipping point" (another of Gladwell's mantras), and grow like crazy in a short period of time.

The point about finding a tribe is truly key. But, as with "correct" practice... finding the "right" tribe is also vital. I remember early on I went to a local photography class taught by a prominent photo journalist in our area. I was stoked about him teaching a class. It was full of a bunch of grandmatogs (nothing wrong with that, just sayin') and there was me. One of them asked him (him being said guru) if she should shoot in raw or jpeg. He emphatically told us there was no need whatsoever for us to shoot in RAW. I about fell out of my chair. At least I knew that much. Another thing I knew right then was that this was NOT the group for me, and that I would have to abandon local learning and seek it out online. (I live in Podunk, Mississippi). That search is what led me to you and to Project 52. I found a group, for my commercial work, that I could trust and learn from. Hence, why I'm here reading and studying every word!

For my consumer work, I find PPA is a gem, especially the LOOP forums, but also their Education area. I know PPA is not very highly thought of inside P52, but for me it's been invaluable for many things, and compliments my commercial photography, and vice-versa. Finally, the "Imitate - Assimilate - Innovate" Principle has been one that you've taught and that truly is a foundational principle of my approach to learning, growing and developing my own style. Thanks for all you do.